Designs for the Pluriverse

Arturo Escobar's Manifesto for Radical Interdependence, Autonomy and the Making of Worlds.

Content Map

2024

In a world increasingly dominated by homogenizing forces of globalization and neoliberal capitalism, Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" emerges as a beacon for alternative ways of being and knowing. Escobar, a Colombian anthropologist and professor, draws from his experiences in the Global South to challenge the prevailing Western paradigms that often marginalize diverse worldviews. His work invites us to reimagine design—not just as a tool for creating objects or systems—but as a practice deeply intertwined with cultural, social, and ecological dimensions of life.

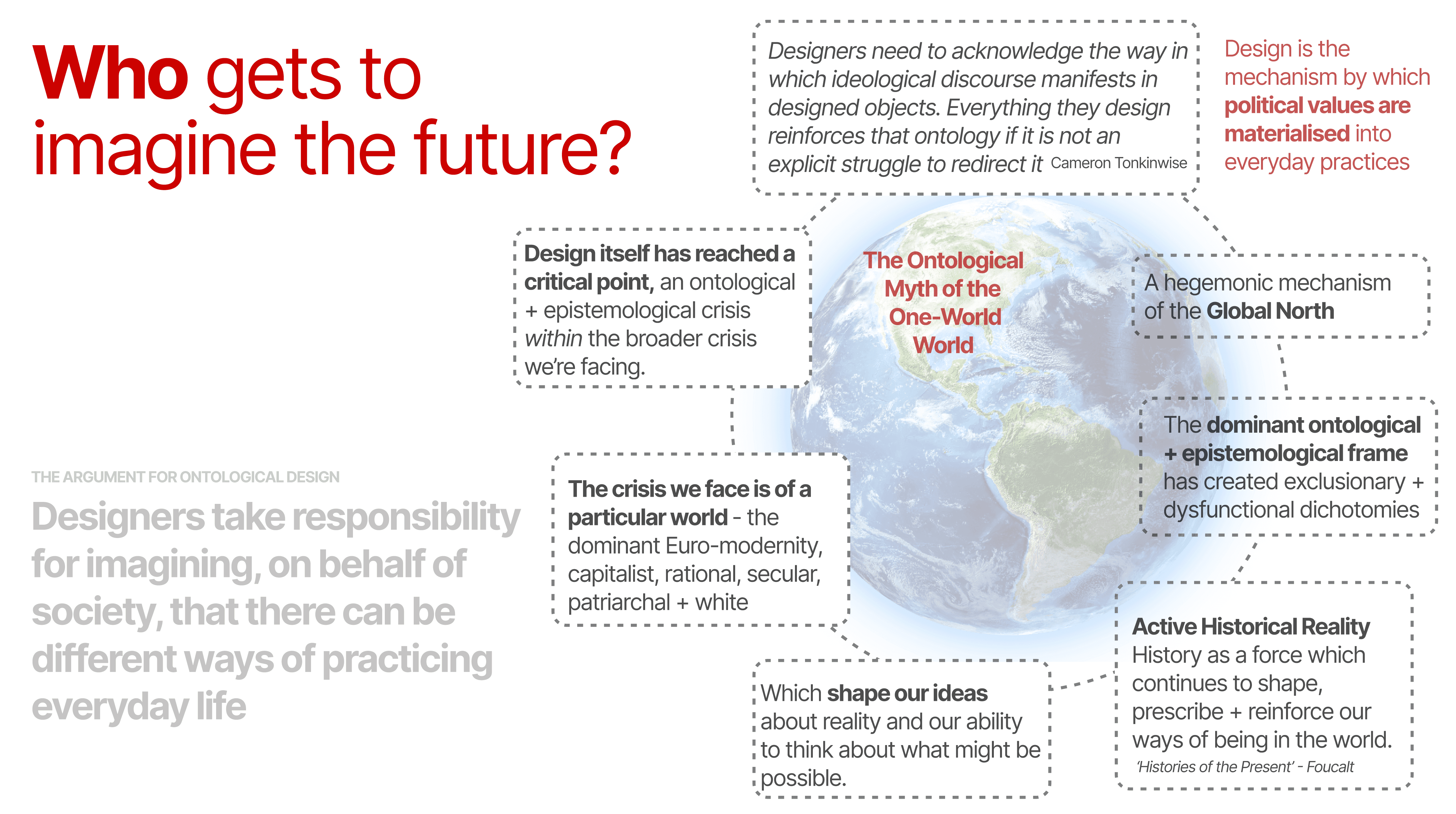

The One-World World Problem

At the heart of Escobar's critique is the concept of the One-World World (OWW), a term borrowed from philosopher John Law. The OWW represents the dominant Western worldview that assumes a single, objective reality—often at the expense of other ways of understanding the world. This hegemonic perspective imposes its own values and systems, effectively silencing alternative epistemologies and ontologies.

The OWW manifests through dysfunctional dichotomies that separate:

Humans from nature

Subject from object

Mind from body

Reason from emotion

Living from inanimate

Human from non-human

Organic from inorganic

These binaries not only limit our understanding but also perpetuate a worldview that justifies the exploitation and marginalization of both people and the environment.

Ontological Design: Resisting the One-World Ontology

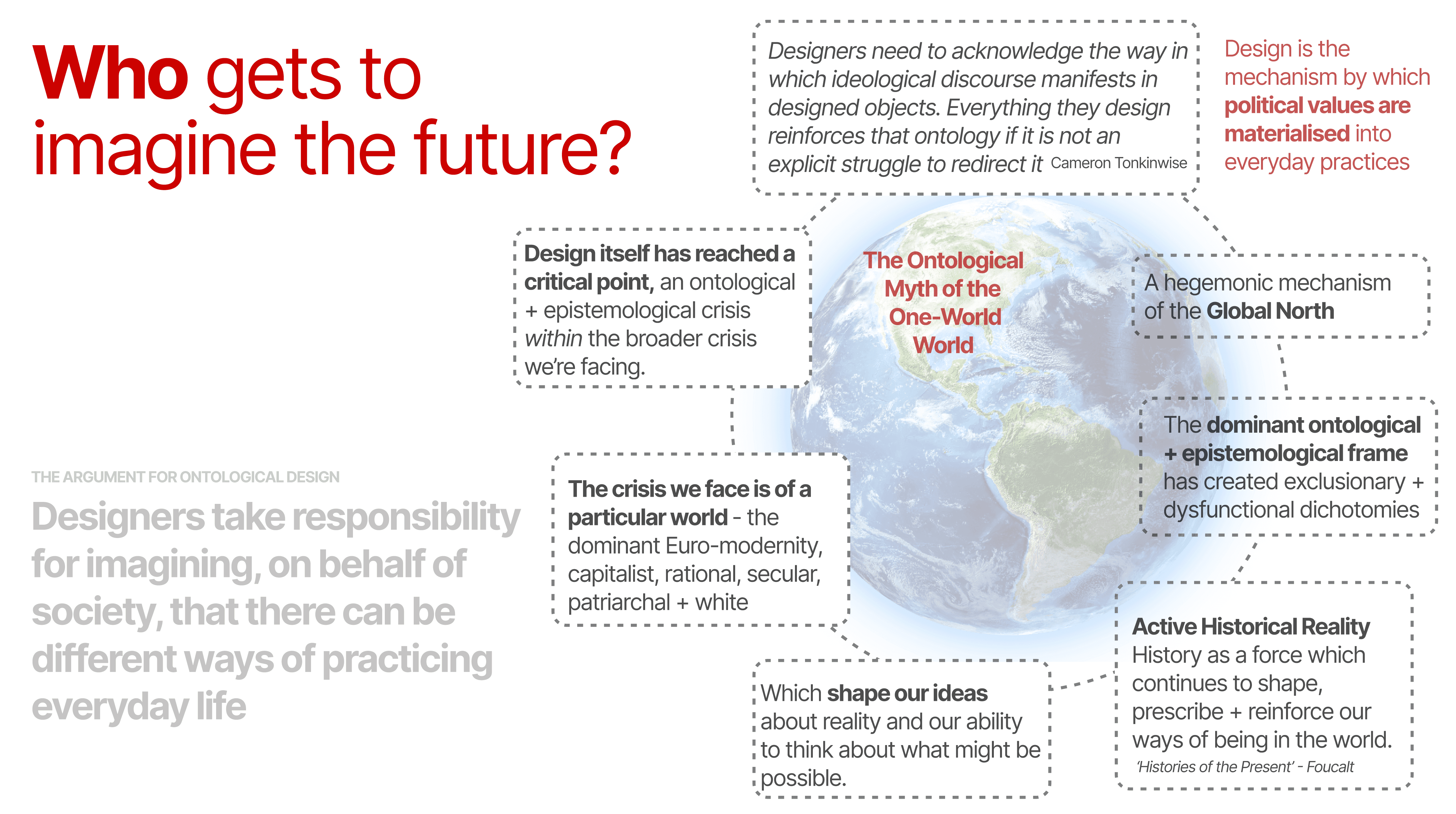

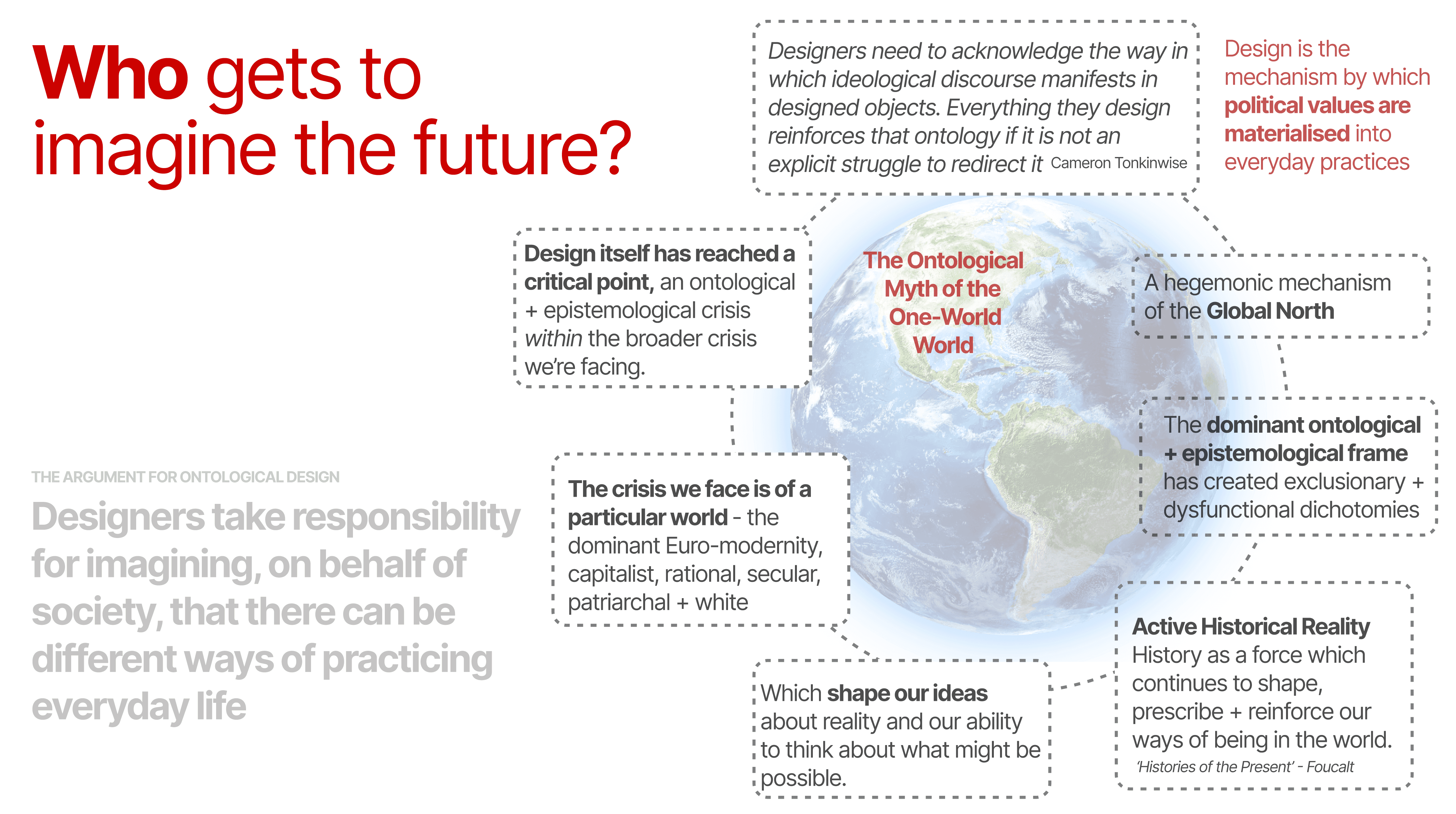

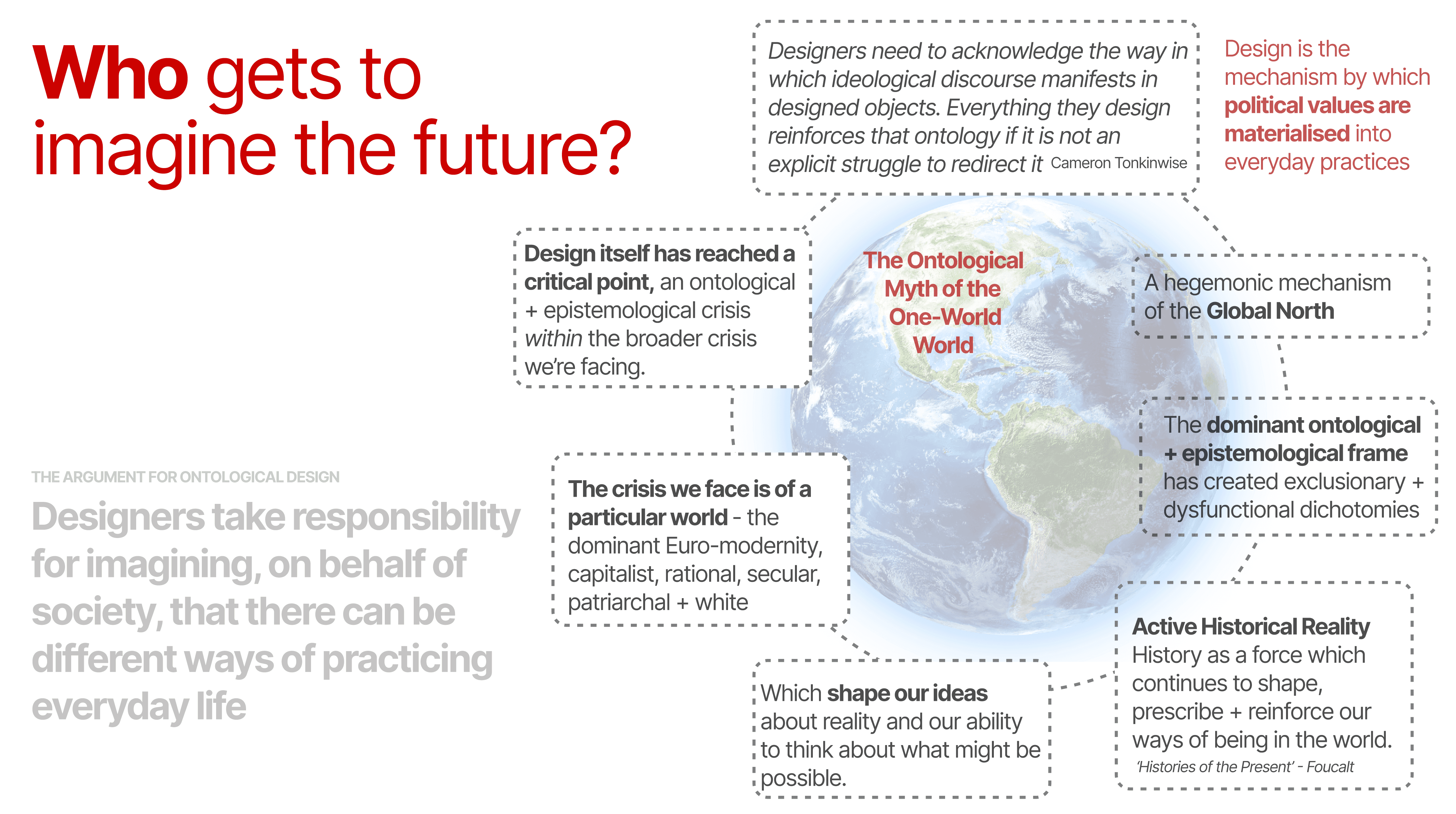

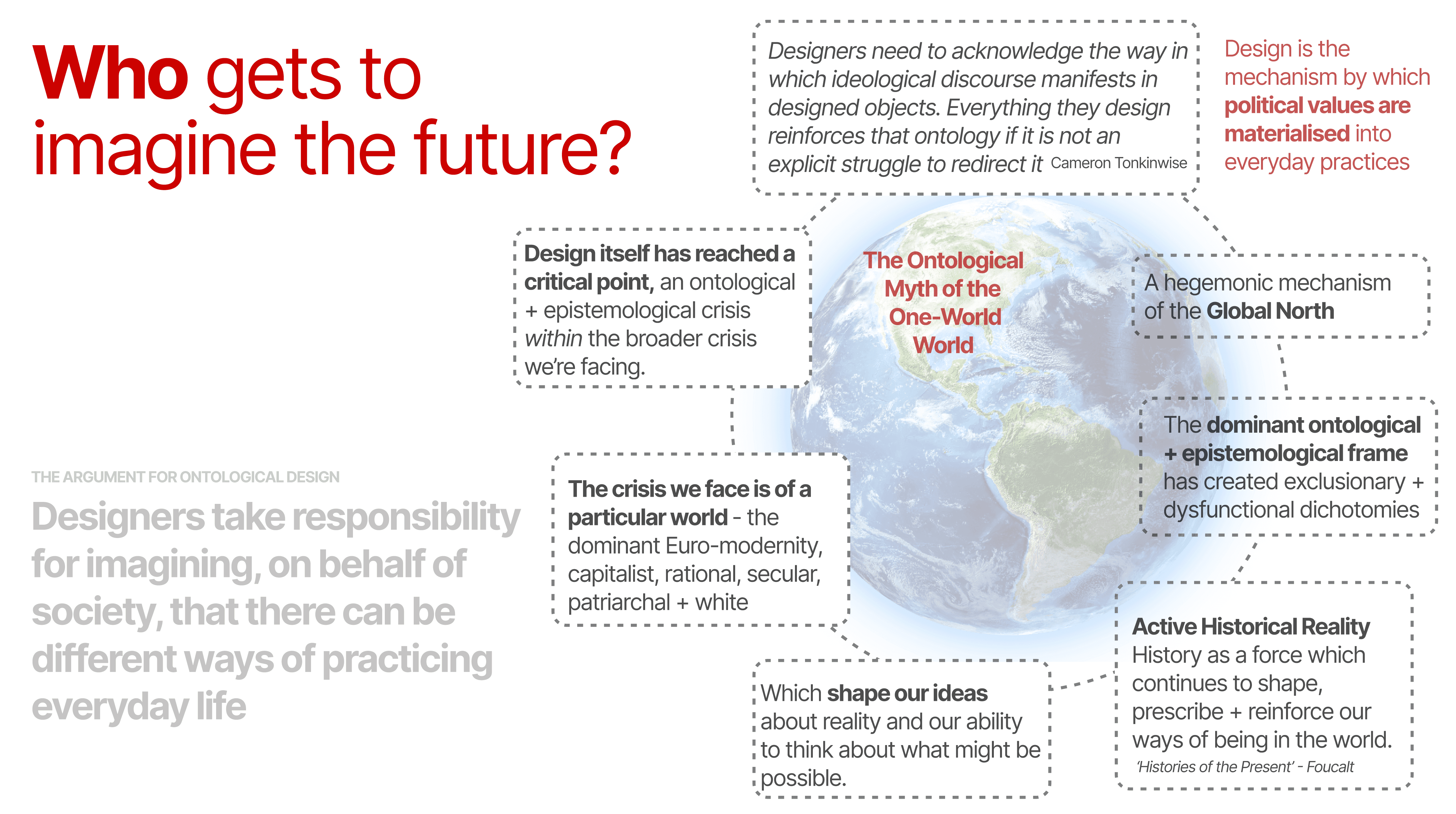

Escobar advocates for ontological design, a practice that recognizes the power of design in shaping our realities. By asking critical questions like "Which design?" "What world?" and "What reality?" we begin to see design not as a neutral or purely functional activity but as a world-making practice.

Designers, according to Escobar, must become aware of the "active historical reality"—the ways in which history continues to shape and constrain present-day behaviors and systems. Similar to Michel Foucault's concept of "histories of the present," Escobar emphasizes that our current social structures are products of historical processes that can and should be questioned.

"Designers need to understand the way an ideological discourse manifests in designed objects and built environments. They are only ever designing within wider ontological settings, and everything they design reinforces that ontology if it is not an explicit struggle to redirect it." Cameron Tonkinwise

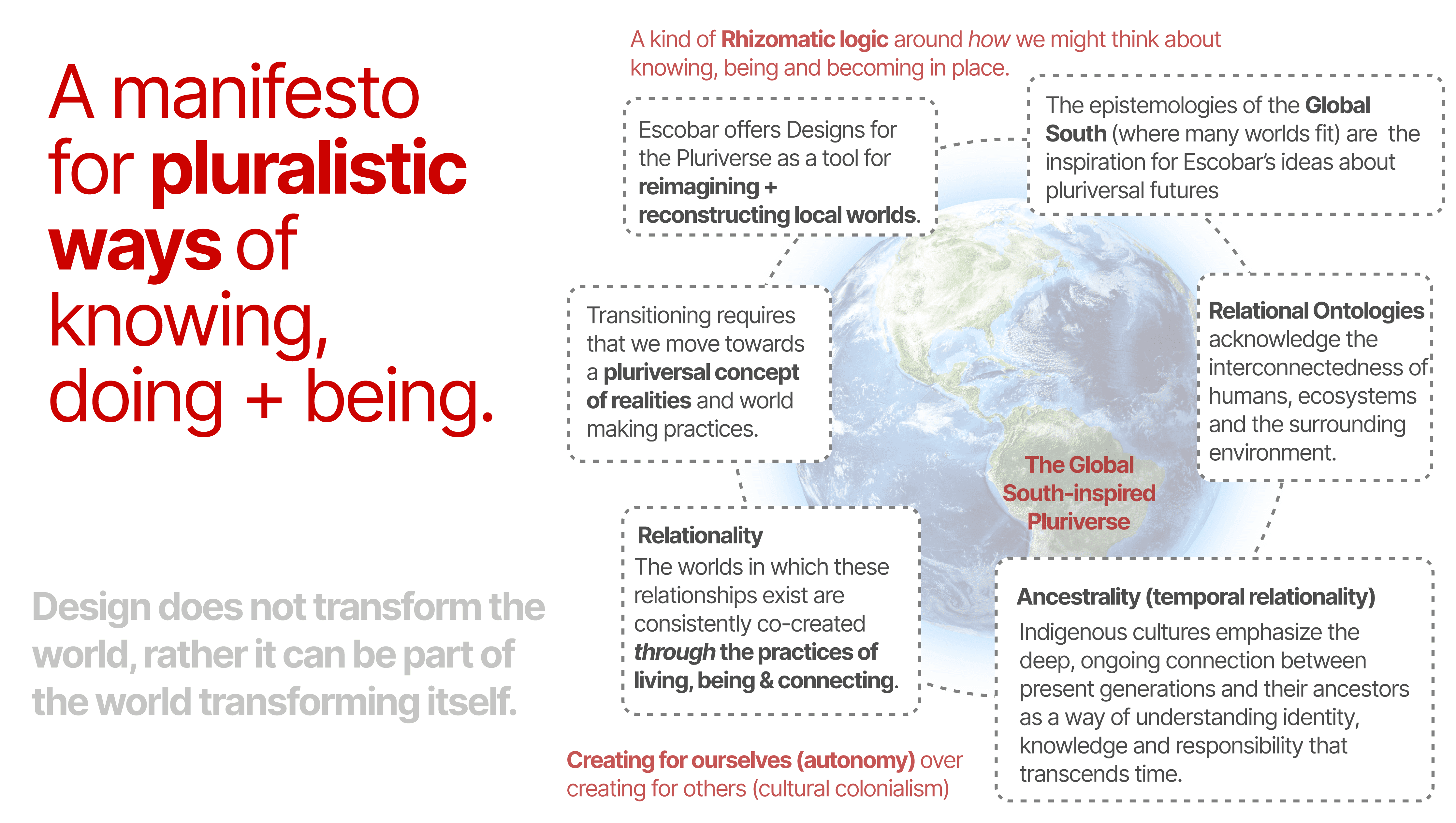

Epistemologies of the Global South and the Pluriverse

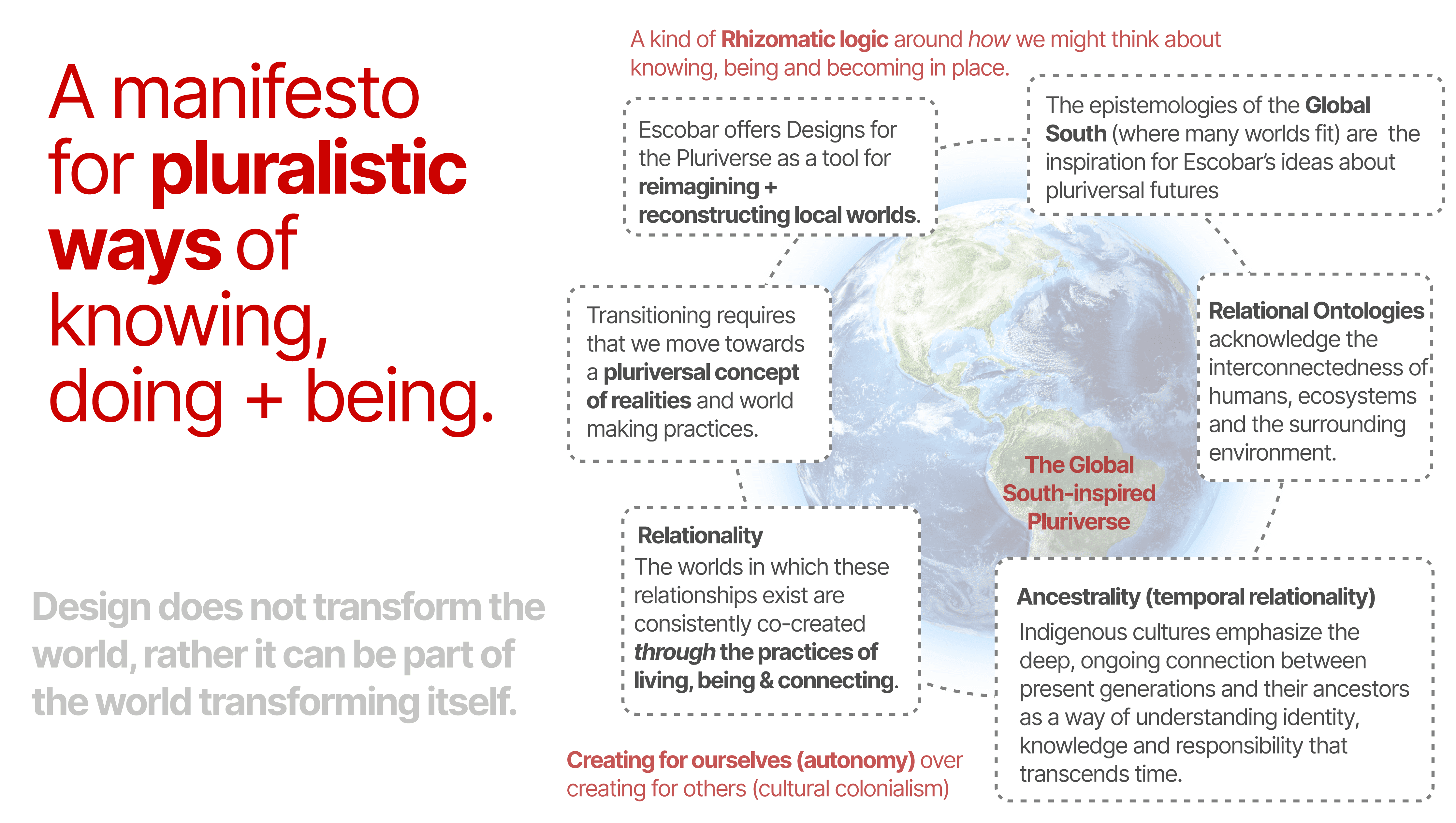

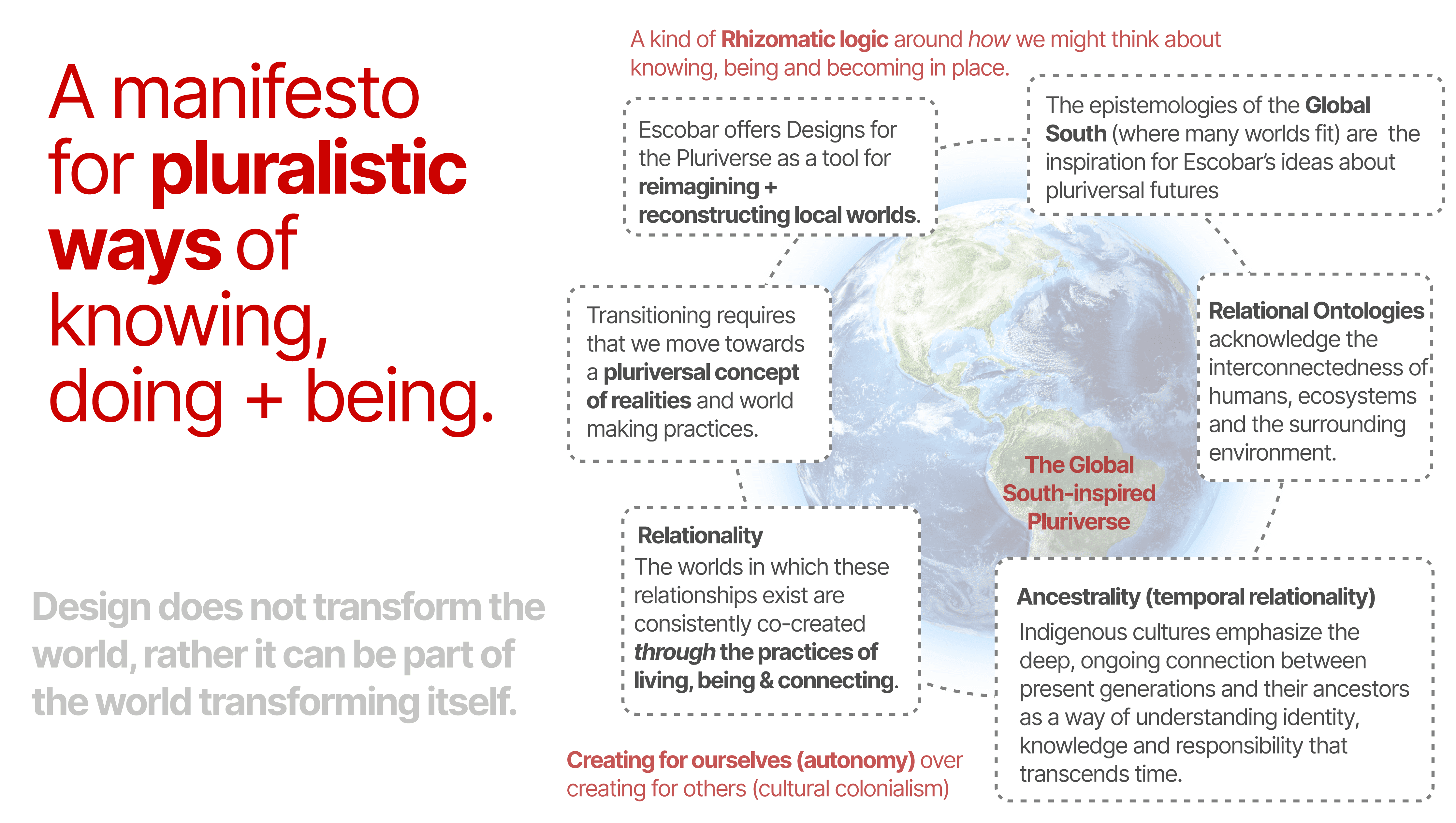

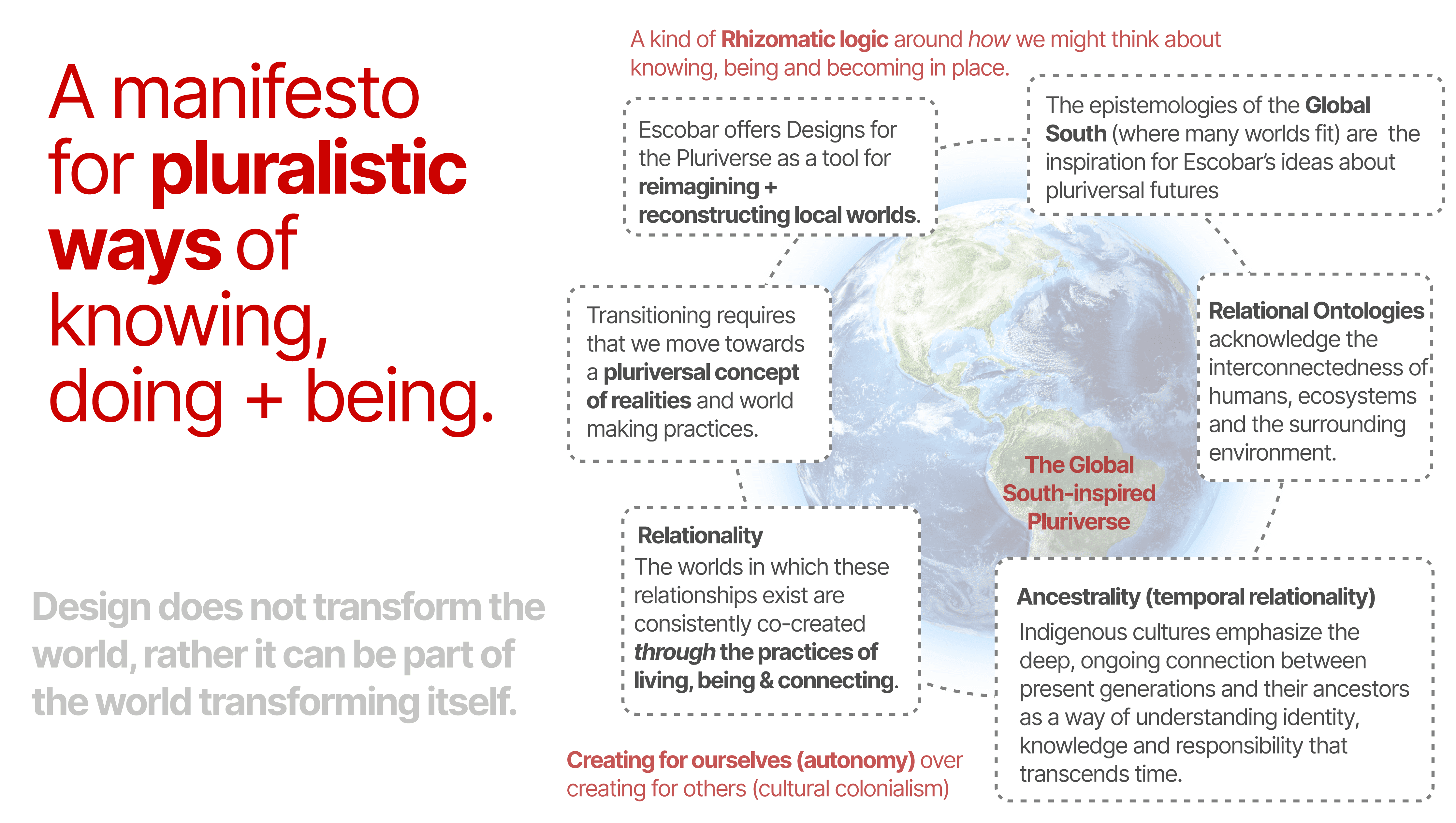

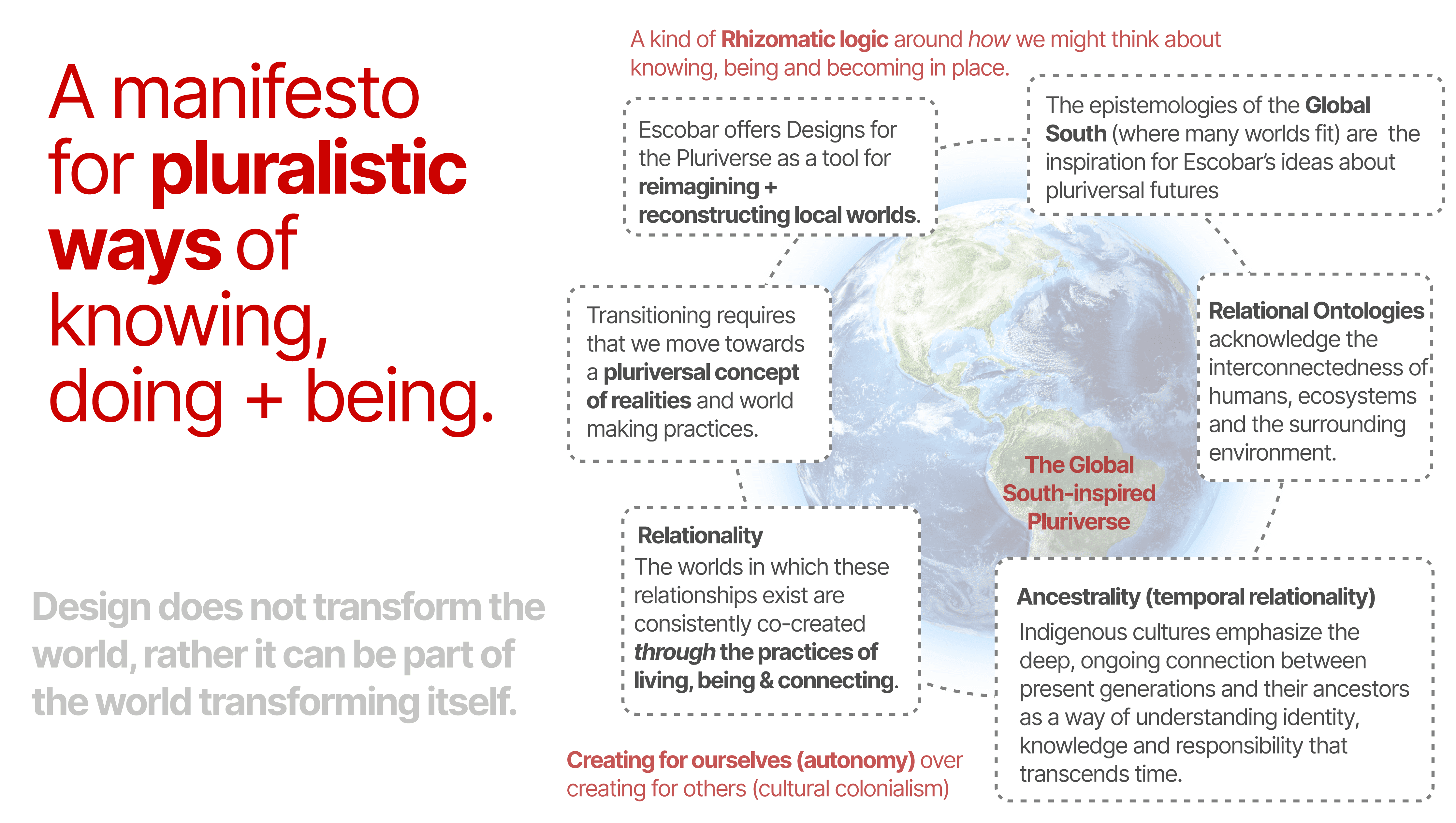

In response to the OWW, Escobar highlights the Epistemologies of the Global South—local struggles and knowledge systems that strive to re-establish balance with nature and among humans and non-humans. These epistemologies challenge the normative dualisms of Western thinking and emphasize relational ontologies where meaning arises through connections with others.

The concept of the pluriverse emerges from this understanding—a world where many worlds fit, embracing a diversity of beings, knowledges, and practices. Moving beyond the Age of Enlightenment's obsession with rationalism and science, Escobar calls for the inclusion of intuition, feelings, and emotions as valid forms of understanding.

He posits that the lived experiences of marginalized communities often create conditions for radically different modes of participation and action-oriented design. Here, local knowledge and insights become the starting point, not an afterthought.

Relational Ontologies and Ancestrality

Relational ontologies recognize that people, objects, and concepts are defined by their relationships and interactions rather than existing as isolated entities. For example, a person's identity is shaped by their relationships with family, community, and environment.

In many indigenous cultures, ancestrality plays a crucial role. Ancestors are seen as an active presence influencing how people relate to land, community, traditions, and the future. This perspective underscores the urgency of integrating ancient wisdom into modern times.

Design as a Space for Transformation

Escobar envisions design as a space for transformation—not as an external force acting upon the world but as an integral part of the world transforming itself. This approach moves design away from a colonizing posture and towards one that acknowledges autonomy, agency, and interdependence.

He advocates for design as a potential mechanism of plurality, by recognizing that design is neither neutral nor universal, we can use it as a tool for intentional creation that includes diverse knowledges and experiences within specific contexts.

Escobar invites us to consider the shift from creating for others—a patriarchal and colonial approach—to creating with others, and ultimately, to all of us creating for ourselves with each other, locating imagination within the context of community, autonomy, and mutual interdependence.

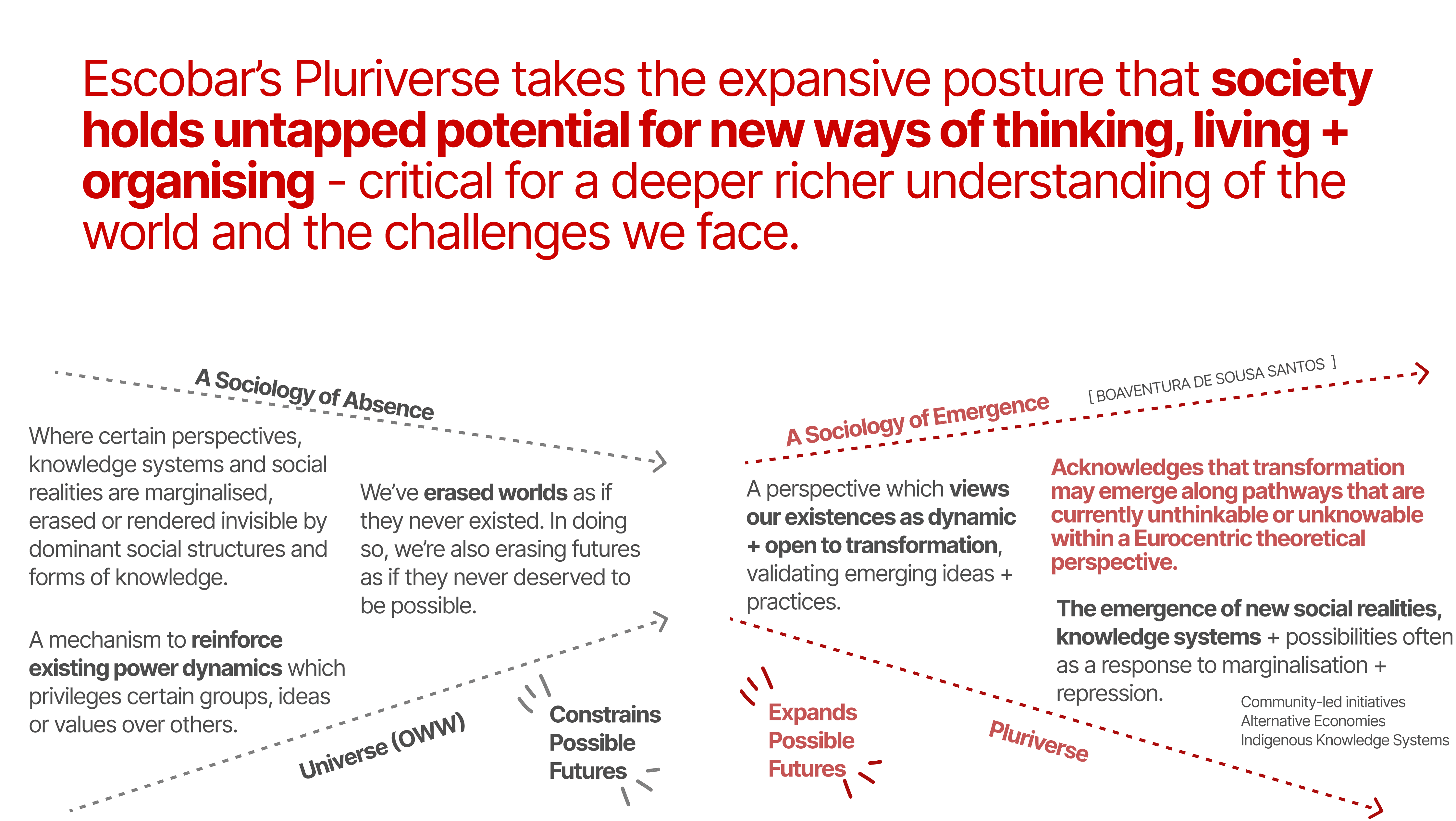

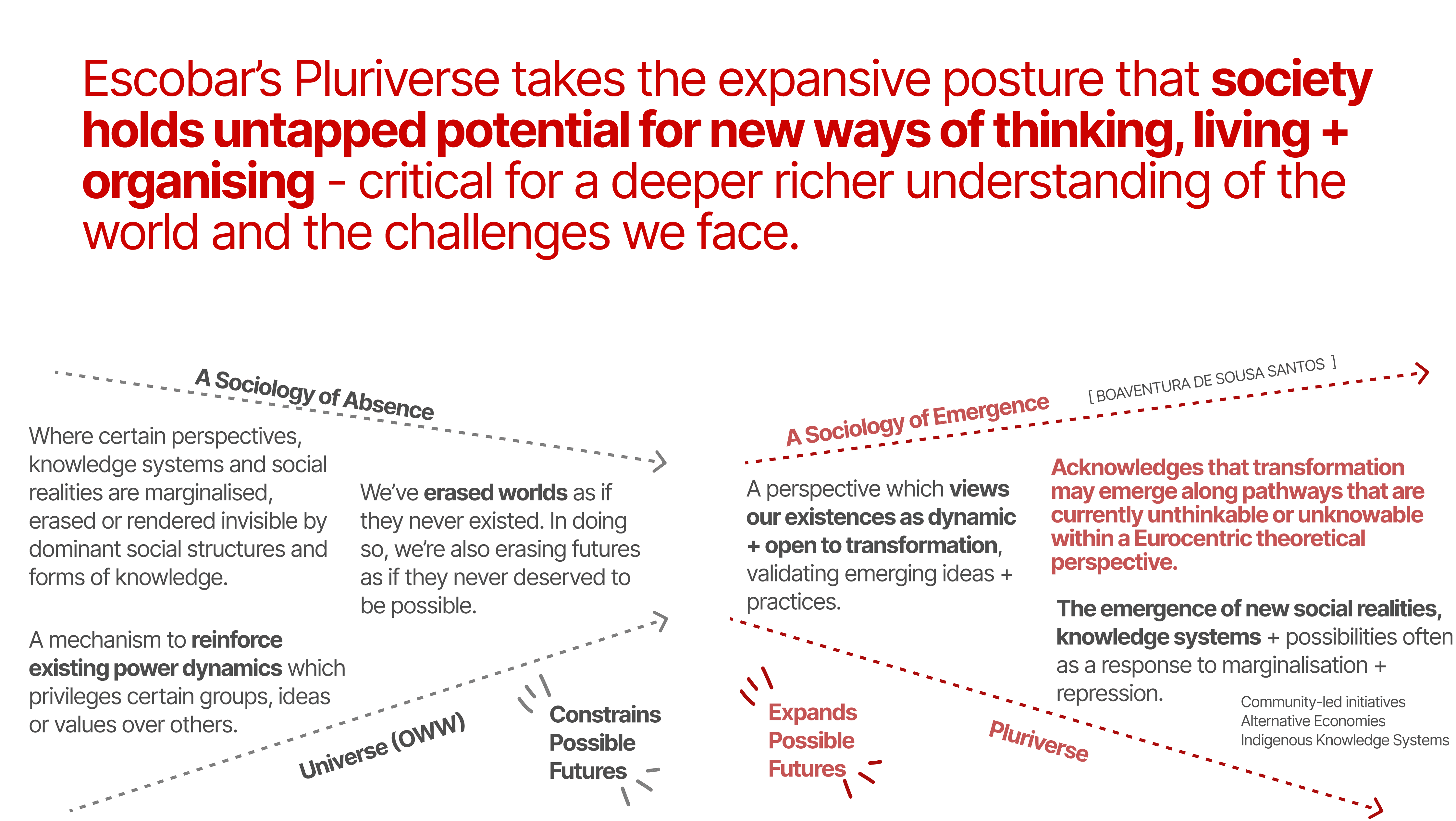

Sociology of Absence and Emergence

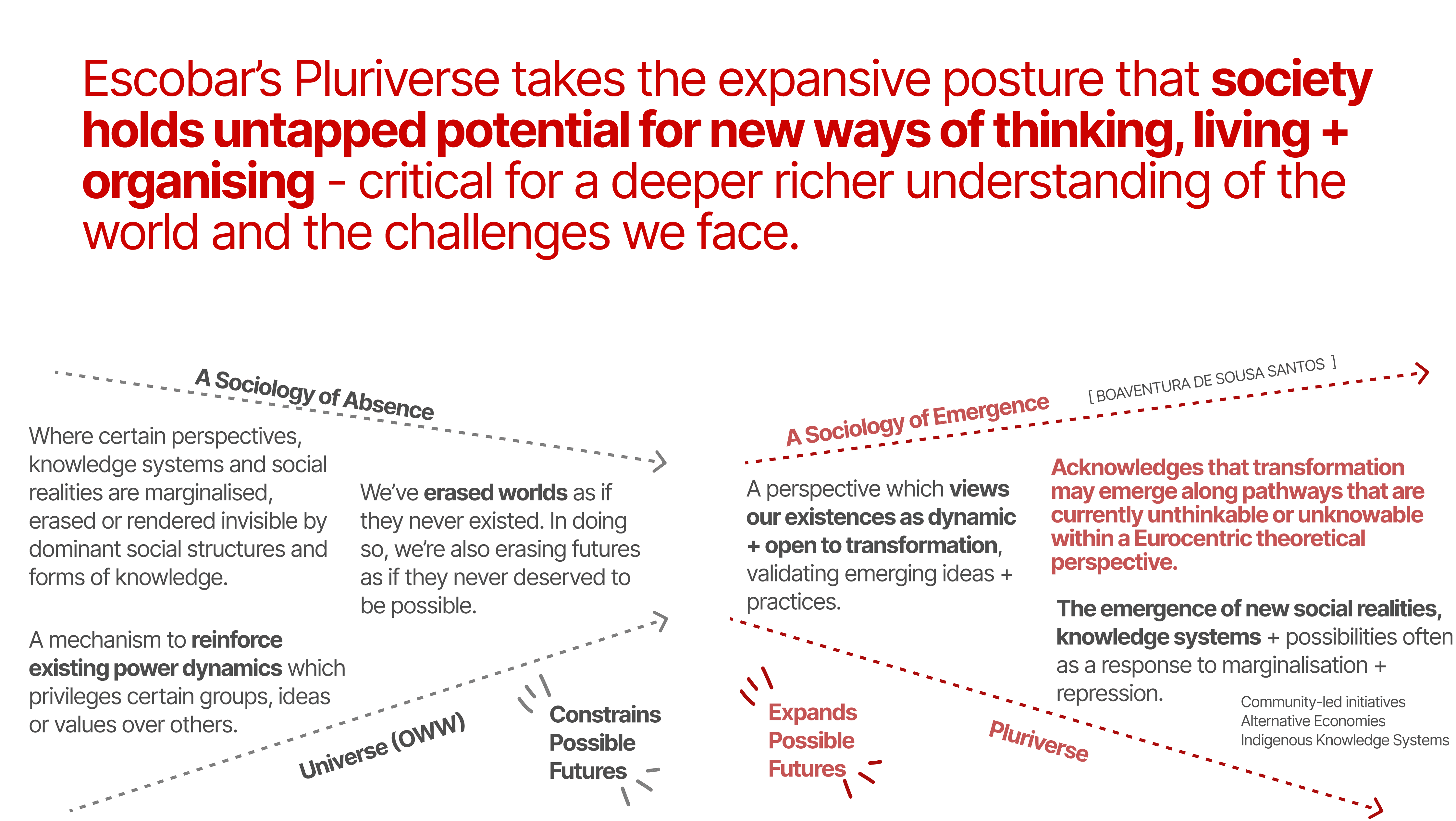

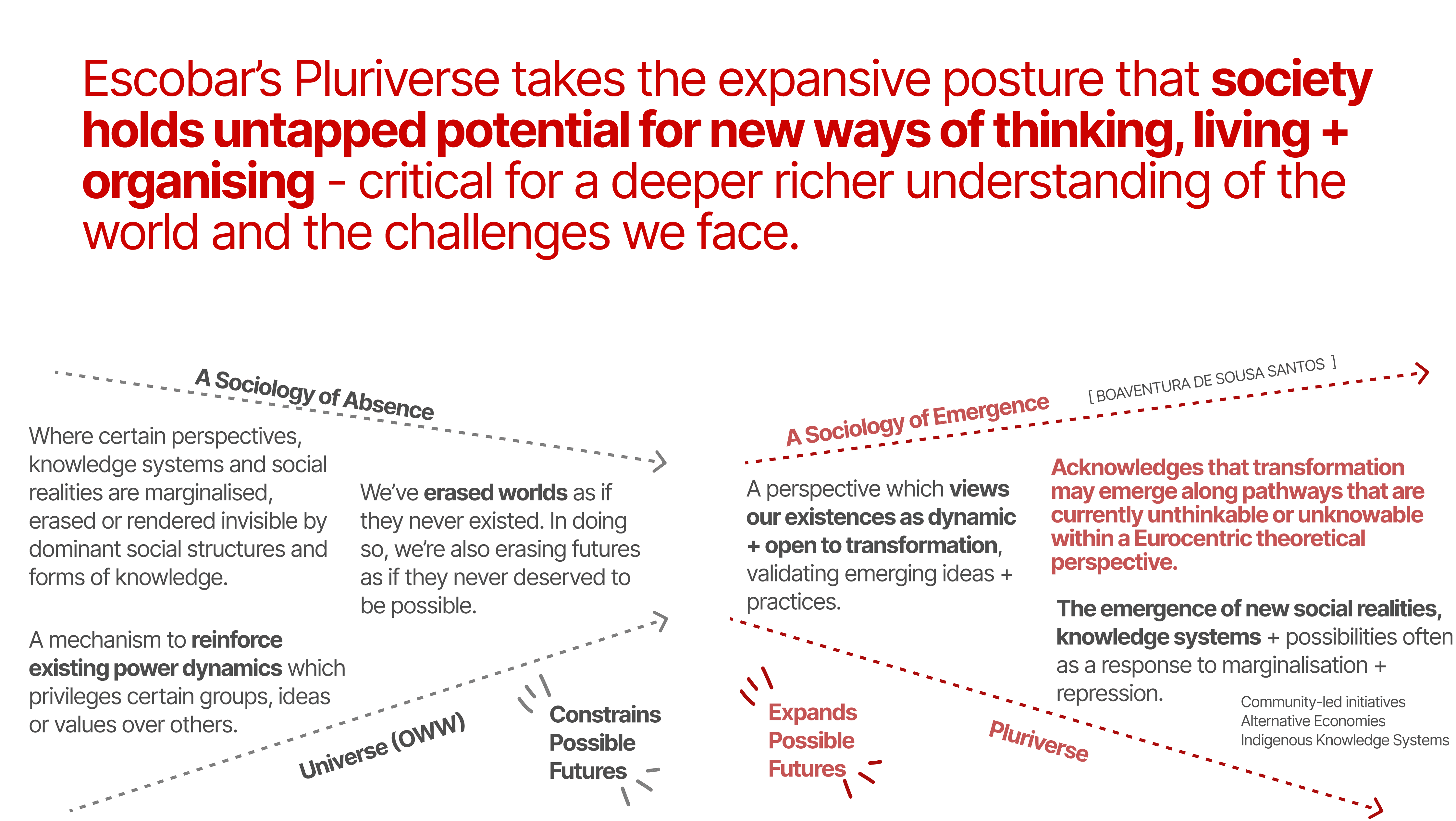

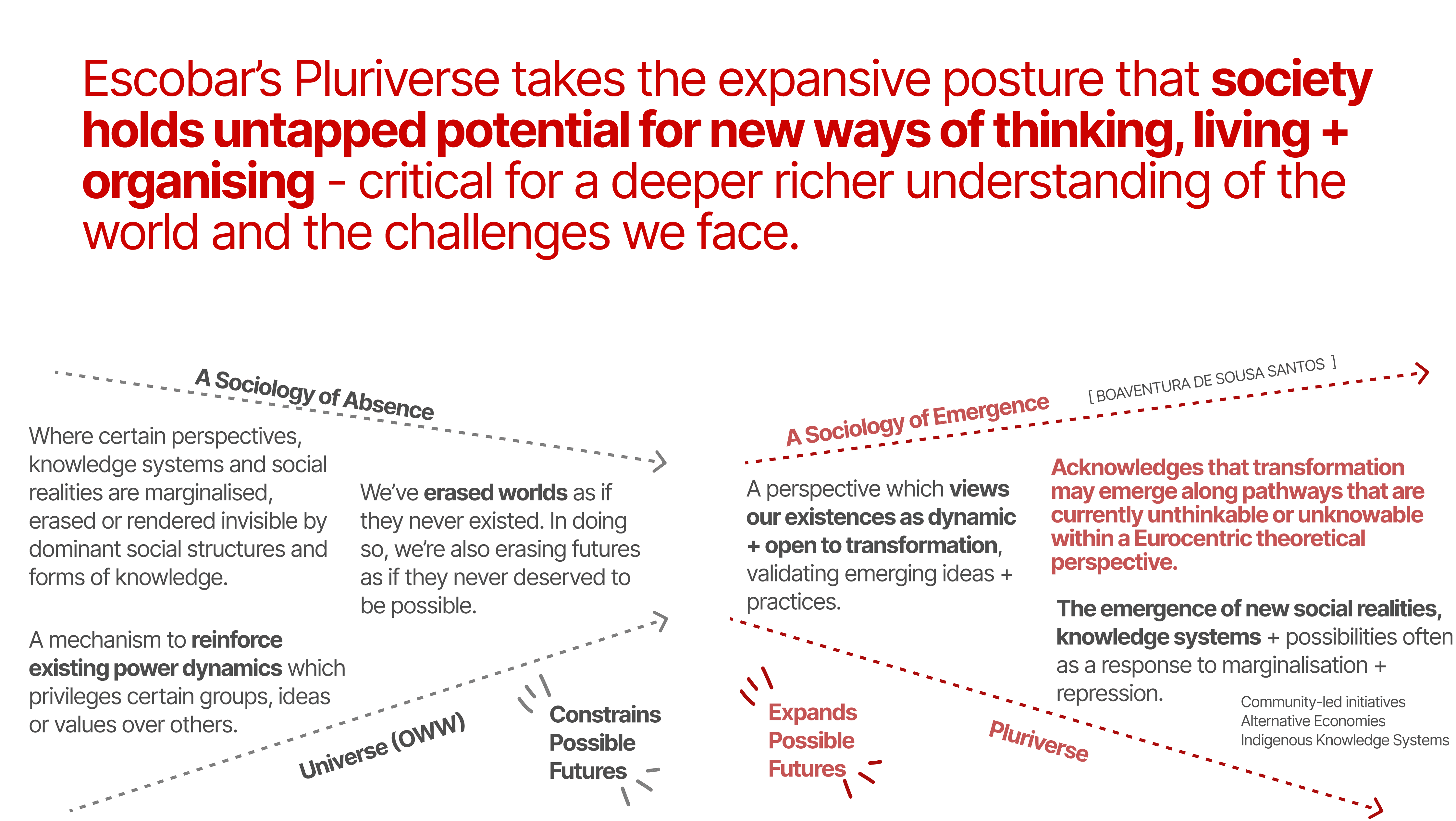

Escobar introduces Boaventura de Sousa Santos' concepts of the "sociology of absences" and the "sociology of emergence."

Sociology of Absence: This addresses how certain perspectives, knowledge systems, and social realities are marginalized or erased by dominant structures. These absences are not natural or accidental; they are actively produced to maintain existing power dynamics.

Sociology of Emergence: This focuses on the untapped potential within society for new ways of thinking, organizing, and living. It seeks to identify and legitimize emerging ideas and practices that challenge the status quo.

By recognizing these dynamics, we can begin to recover and include diverse perspectives, fostering a more equitable and comprehensive understanding of the world.

Implications for Design and Futures

Transitioning towards a pluriversal approach requires embracing pluralism in our design practices. This involves:

Challenging the singular, universal future often implicit in mainstream thinking.

Decentralizing Western perspectives to imagine and support multiple futures.

Prioritizing context-specific futures grounded in local knowledge systems.

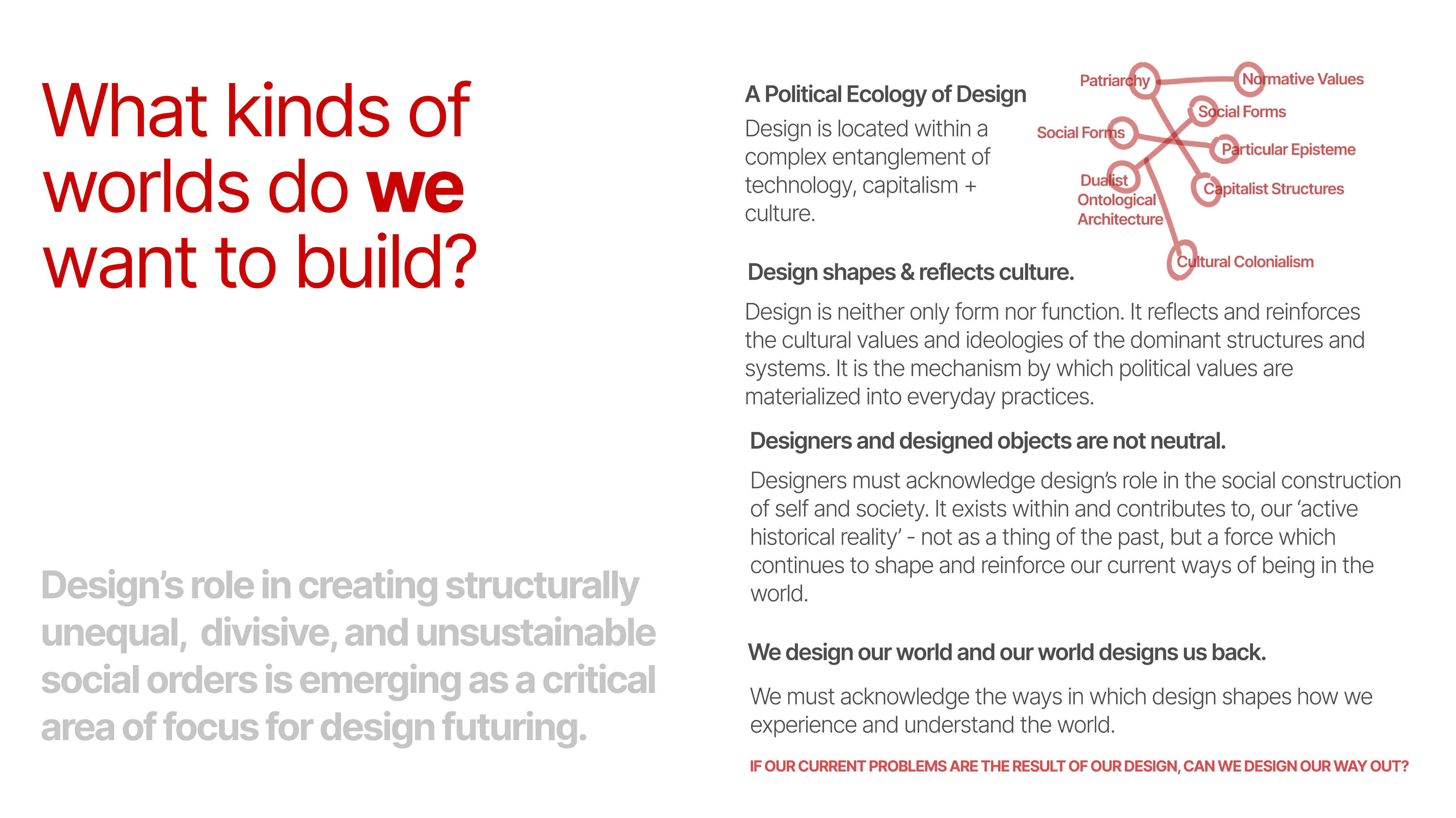

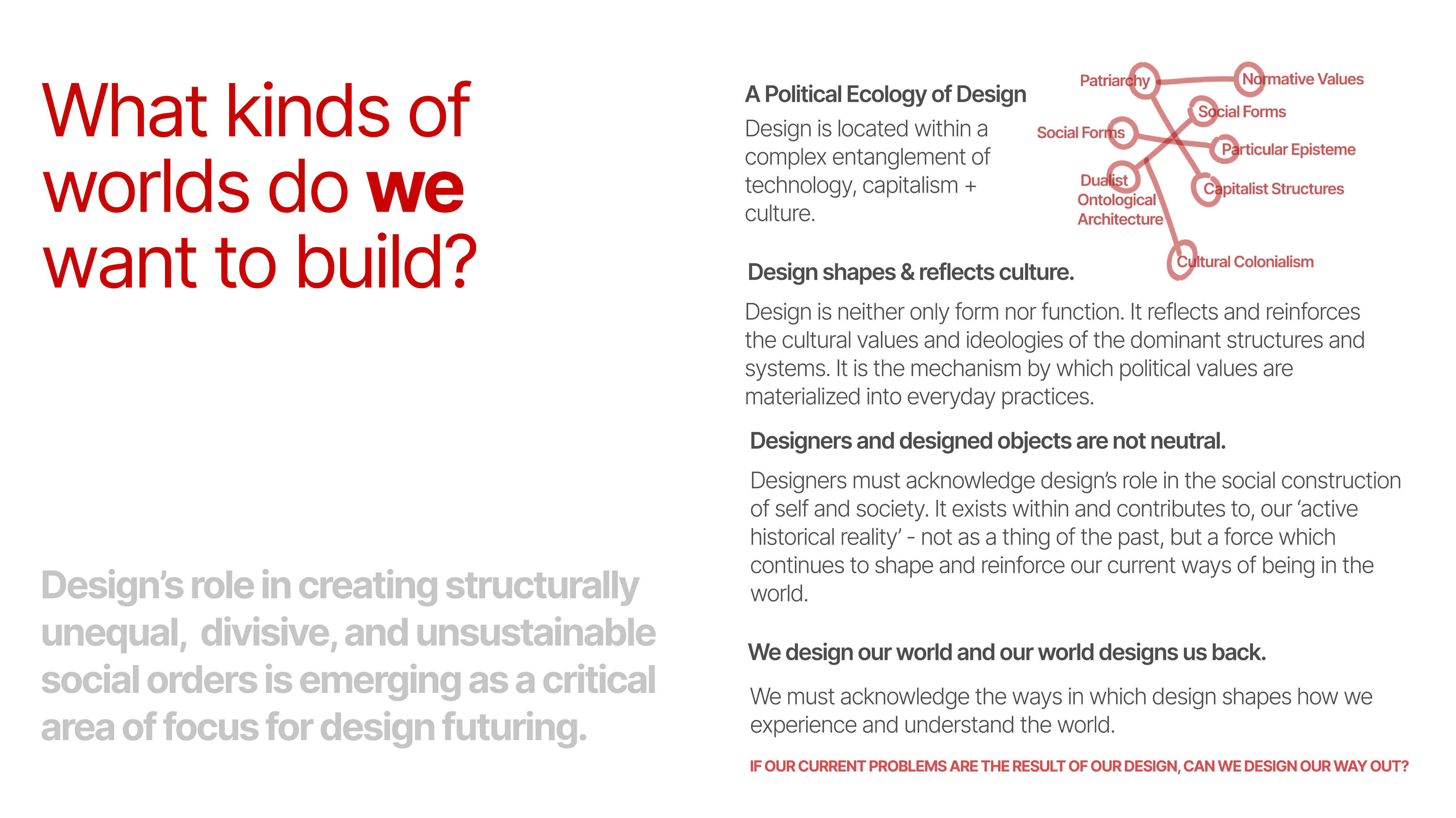

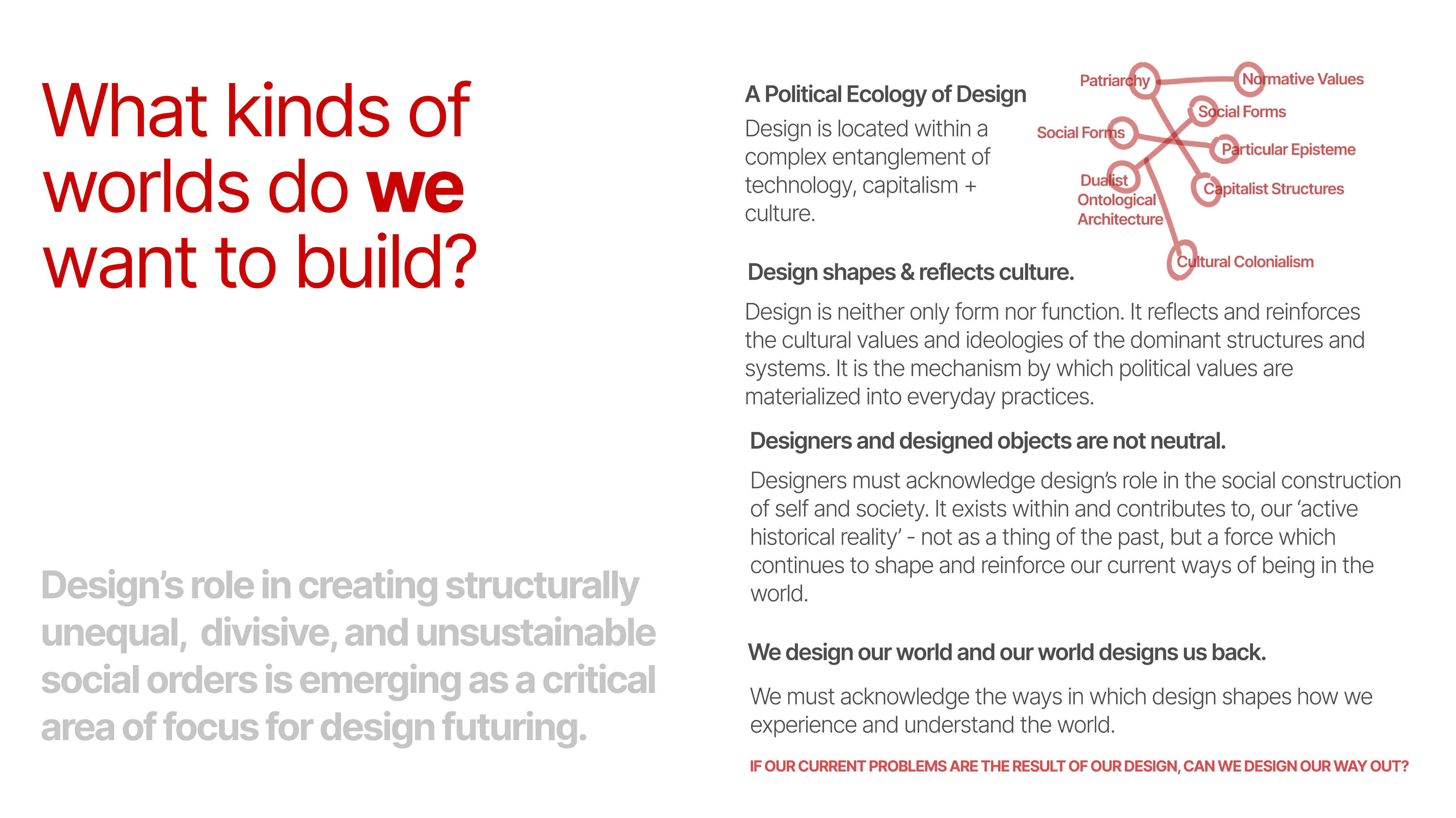

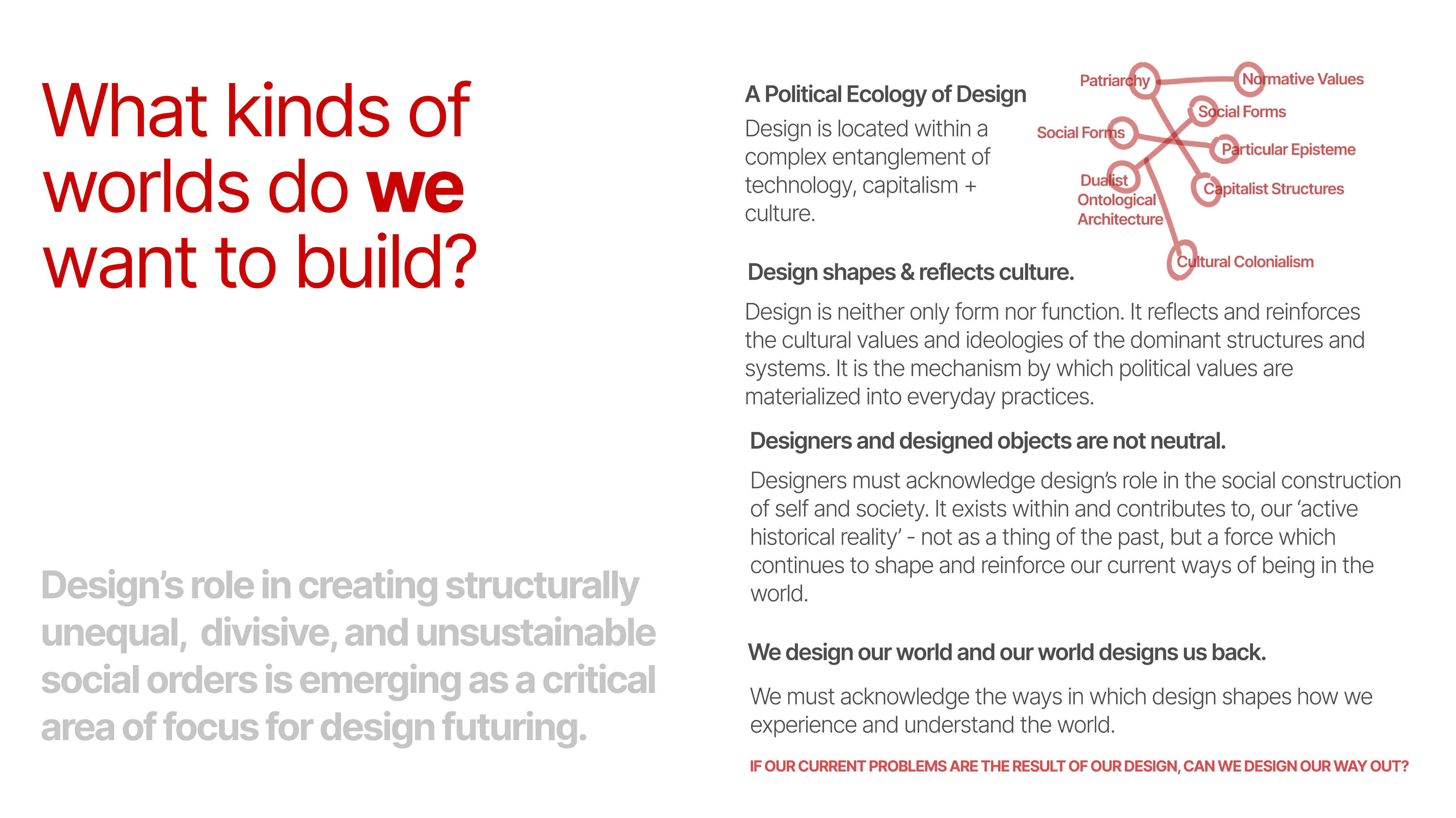

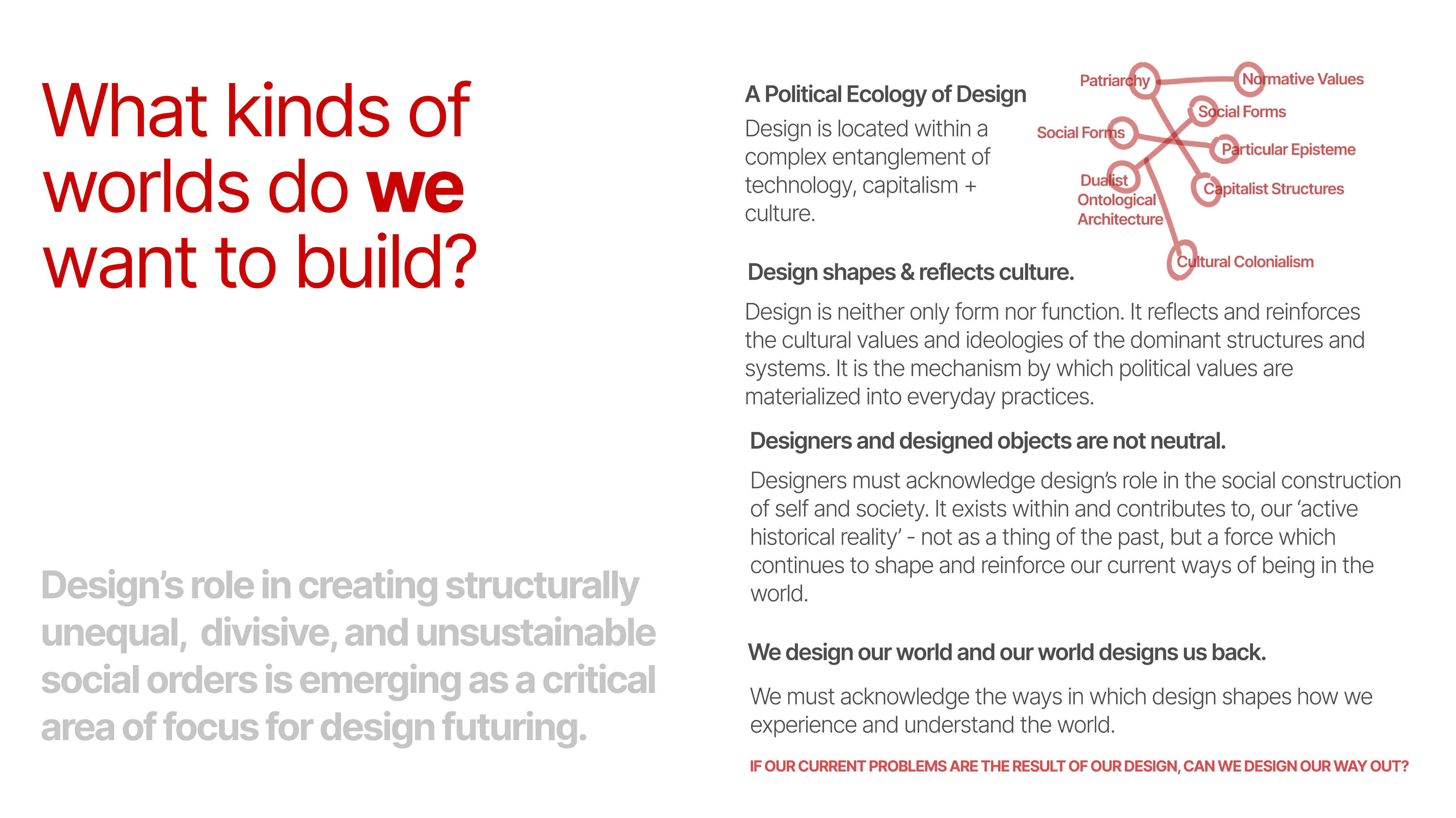

Escobar reframes design as a futures practice, advocating for ontological design that acknowledges how design shapes our experiences and understandings of the world. He explores a "political ecology of design" that moves beyond Western epistemological structures and addresses intersections with race, gender, and colonialism.

Design Shapes and Reflects Culture

Design is inherently political. It plays a central role in our social construction of self and society. The objects and environments we create influence our behaviors, relationships, and even our identities.

As Winston Churchill famously said, "We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us." Similarly, Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa noted that a building is not an end in itself but "conditions and transforms the human experience of reality."

Escobar invites designers to to be mindful of the ideological discourses manifested in design work, and in doing so, being conscious of inadvertently reinforcing dominant ontologies and instead contributing to the imagining of possible futures which centre on inclusive and diverse worlds.

Designing for a Pluriverse

Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" challenges us to rethink design's role in society fundamentally. It calls for a shift from a singular, hegemonic worldview to one that embraces the multiplicity of human experiences and knowledge systems. By adopting a pluriversal approach, we can begin to imagine and create worlds where many worlds fit—a reality that is richer, more equitable, and more responsive to the diverse needs of all beings.

To reimagine what is possible is one of the most important cultural and political acts we can engage in at present.

Arturo Escobar

In embracing this vision, designers become not just creators of objects or systems but facilitators of transformative processes that honor the complexity and diversity of life itself.

In a world increasingly dominated by homogenizing forces of globalization and neoliberal capitalism, Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" emerges as a beacon for alternative ways of being and knowing. Escobar, a Colombian anthropologist and professor, draws from his experiences in the Global South to challenge the prevailing Western paradigms that often marginalize diverse worldviews. His work invites us to reimagine design—not just as a tool for creating objects or systems—but as a practice deeply intertwined with cultural, social, and ecological dimensions of life.

The One-World World Problem

At the heart of Escobar's critique is the concept of the One-World World (OWW), a term borrowed from philosopher John Law. The OWW represents the dominant Western worldview that assumes a single, objective reality—often at the expense of other ways of understanding the world. This hegemonic perspective imposes its own values and systems, effectively silencing alternative epistemologies and ontologies.

The OWW manifests through dysfunctional dichotomies that separate:

Humans from nature

Subject from object

Mind from body

Reason from emotion

Living from inanimate

Human from non-human

Organic from inorganic

These binaries not only limit our understanding but also perpetuate a worldview that justifies the exploitation and marginalization of both people and the environment.

Ontological Design: Resisting the One-World Ontology

Escobar advocates for ontological design, a practice that recognizes the power of design in shaping our realities. By asking critical questions like "Which design?" "What world?" and "What reality?" we begin to see design not as a neutral or purely functional activity but as a world-making practice.

Designers, according to Escobar, must become aware of the "active historical reality"—the ways in which history continues to shape and constrain present-day behaviors and systems. Similar to Michel Foucault's concept of "histories of the present," Escobar emphasizes that our current social structures are products of historical processes that can and should be questioned.

"Designers need to understand the way an ideological discourse manifests in designed objects and built environments. They are only ever designing within wider ontological settings, and everything they design reinforces that ontology if it is not an explicit struggle to redirect it." Cameron Tonkinwise

Epistemologies of the Global South and the Pluriverse

In response to the OWW, Escobar highlights the Epistemologies of the Global South—local struggles and knowledge systems that strive to re-establish balance with nature and among humans and non-humans. These epistemologies challenge the normative dualisms of Western thinking and emphasize relational ontologies where meaning arises through connections with others.

The concept of the pluriverse emerges from this understanding—a world where many worlds fit, embracing a diversity of beings, knowledges, and practices. Moving beyond the Age of Enlightenment's obsession with rationalism and science, Escobar calls for the inclusion of intuition, feelings, and emotions as valid forms of understanding.

He posits that the lived experiences of marginalized communities often create conditions for radically different modes of participation and action-oriented design. Here, local knowledge and insights become the starting point, not an afterthought.

Relational Ontologies and Ancestrality

Relational ontologies recognize that people, objects, and concepts are defined by their relationships and interactions rather than existing as isolated entities. For example, a person's identity is shaped by their relationships with family, community, and environment.

In many indigenous cultures, ancestrality plays a crucial role. Ancestors are seen as an active presence influencing how people relate to land, community, traditions, and the future. This perspective underscores the urgency of integrating ancient wisdom into modern times.

Design as a Space for Transformation

Escobar envisions design as a space for transformation—not as an external force acting upon the world but as an integral part of the world transforming itself. This approach moves design away from a colonizing posture and towards one that acknowledges autonomy, agency, and interdependence.

He advocates for design as a potential mechanism of plurality, by recognizing that design is neither neutral nor universal, we can use it as a tool for intentional creation that includes diverse knowledges and experiences within specific contexts.

Escobar invites us to consider the shift from creating for others—a patriarchal and colonial approach—to creating with others, and ultimately, to all of us creating for ourselves with each other, locating imagination within the context of community, autonomy, and mutual interdependence.

Sociology of Absence and Emergence

Escobar introduces Boaventura de Sousa Santos' concepts of the "sociology of absences" and the "sociology of emergence."

Sociology of Absence: This addresses how certain perspectives, knowledge systems, and social realities are marginalized or erased by dominant structures. These absences are not natural or accidental; they are actively produced to maintain existing power dynamics.

Sociology of Emergence: This focuses on the untapped potential within society for new ways of thinking, organizing, and living. It seeks to identify and legitimize emerging ideas and practices that challenge the status quo.

By recognizing these dynamics, we can begin to recover and include diverse perspectives, fostering a more equitable and comprehensive understanding of the world.

Implications for Design and Futures

Transitioning towards a pluriversal approach requires embracing pluralism in our design practices. This involves:

Challenging the singular, universal future often implicit in mainstream thinking.

Decentralizing Western perspectives to imagine and support multiple futures.

Prioritizing context-specific futures grounded in local knowledge systems.

Escobar reframes design as a futures practice, advocating for ontological design that acknowledges how design shapes our experiences and understandings of the world. He explores a "political ecology of design" that moves beyond Western epistemological structures and addresses intersections with race, gender, and colonialism.

Design Shapes and Reflects Culture

Design is inherently political. It plays a central role in our social construction of self and society. The objects and environments we create influence our behaviors, relationships, and even our identities.

As Winston Churchill famously said, "We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us." Similarly, Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa noted that a building is not an end in itself but "conditions and transforms the human experience of reality."

Escobar invites designers to to be mindful of the ideological discourses manifested in design work, and in doing so, being conscious of inadvertently reinforcing dominant ontologies and instead contributing to the imagining of possible futures which centre on inclusive and diverse worlds.

Designing for a Pluriverse

Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" challenges us to rethink design's role in society fundamentally. It calls for a shift from a singular, hegemonic worldview to one that embraces the multiplicity of human experiences and knowledge systems. By adopting a pluriversal approach, we can begin to imagine and create worlds where many worlds fit—a reality that is richer, more equitable, and more responsive to the diverse needs of all beings.

To reimagine what is possible is one of the most important cultural and political acts we can engage in at present.

Arturo Escobar

In embracing this vision, designers become not just creators of objects or systems but facilitators of transformative processes that honor the complexity and diversity of life itself.

In a world increasingly dominated by homogenizing forces of globalization and neoliberal capitalism, Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" emerges as a beacon for alternative ways of being and knowing. Escobar, a Colombian anthropologist and professor, draws from his experiences in the Global South to challenge the prevailing Western paradigms that often marginalize diverse worldviews. His work invites us to reimagine design—not just as a tool for creating objects or systems—but as a practice deeply intertwined with cultural, social, and ecological dimensions of life.

The One-World World Problem

At the heart of Escobar's critique is the concept of the One-World World (OWW), a term borrowed from philosopher John Law. The OWW represents the dominant Western worldview that assumes a single, objective reality—often at the expense of other ways of understanding the world. This hegemonic perspective imposes its own values and systems, effectively silencing alternative epistemologies and ontologies.

The OWW manifests through dysfunctional dichotomies that separate:

Humans from nature

Subject from object

Mind from body

Reason from emotion

Living from inanimate

Human from non-human

Organic from inorganic

These binaries not only limit our understanding but also perpetuate a worldview that justifies the exploitation and marginalization of both people and the environment.

Ontological Design: Resisting the One-World Ontology

Escobar advocates for ontological design, a practice that recognizes the power of design in shaping our realities. By asking critical questions like "Which design?" "What world?" and "What reality?" we begin to see design not as a neutral or purely functional activity but as a world-making practice.

Designers, according to Escobar, must become aware of the "active historical reality"—the ways in which history continues to shape and constrain present-day behaviors and systems. Similar to Michel Foucault's concept of "histories of the present," Escobar emphasizes that our current social structures are products of historical processes that can and should be questioned.

"Designers need to understand the way an ideological discourse manifests in designed objects and built environments. They are only ever designing within wider ontological settings, and everything they design reinforces that ontology if it is not an explicit struggle to redirect it." Cameron Tonkinwise

Epistemologies of the Global South and the Pluriverse

In response to the OWW, Escobar highlights the Epistemologies of the Global South—local struggles and knowledge systems that strive to re-establish balance with nature and among humans and non-humans. These epistemologies challenge the normative dualisms of Western thinking and emphasize relational ontologies where meaning arises through connections with others.

The concept of the pluriverse emerges from this understanding—a world where many worlds fit, embracing a diversity of beings, knowledges, and practices. Moving beyond the Age of Enlightenment's obsession with rationalism and science, Escobar calls for the inclusion of intuition, feelings, and emotions as valid forms of understanding.

He posits that the lived experiences of marginalized communities often create conditions for radically different modes of participation and action-oriented design. Here, local knowledge and insights become the starting point, not an afterthought.

Relational Ontologies and Ancestrality

Relational ontologies recognize that people, objects, and concepts are defined by their relationships and interactions rather than existing as isolated entities. For example, a person's identity is shaped by their relationships with family, community, and environment.

In many indigenous cultures, ancestrality plays a crucial role. Ancestors are seen as an active presence influencing how people relate to land, community, traditions, and the future. This perspective underscores the urgency of integrating ancient wisdom into modern times.

Design as a Space for Transformation

Escobar envisions design as a space for transformation—not as an external force acting upon the world but as an integral part of the world transforming itself. This approach moves design away from a colonizing posture and towards one that acknowledges autonomy, agency, and interdependence.

He advocates for design as a potential mechanism of plurality, by recognizing that design is neither neutral nor universal, we can use it as a tool for intentional creation that includes diverse knowledges and experiences within specific contexts.

Escobar invites us to consider the shift from creating for others—a patriarchal and colonial approach—to creating with others, and ultimately, to all of us creating for ourselves with each other, locating imagination within the context of community, autonomy, and mutual interdependence.

Sociology of Absence and Emergence

Escobar introduces Boaventura de Sousa Santos' concepts of the "sociology of absences" and the "sociology of emergence."

Sociology of Absence: This addresses how certain perspectives, knowledge systems, and social realities are marginalized or erased by dominant structures. These absences are not natural or accidental; they are actively produced to maintain existing power dynamics.

Sociology of Emergence: This focuses on the untapped potential within society for new ways of thinking, organizing, and living. It seeks to identify and legitimize emerging ideas and practices that challenge the status quo.

By recognizing these dynamics, we can begin to recover and include diverse perspectives, fostering a more equitable and comprehensive understanding of the world.

Implications for Design and Futures

Transitioning towards a pluriversal approach requires embracing pluralism in our design practices. This involves:

Challenging the singular, universal future often implicit in mainstream thinking.

Decentralizing Western perspectives to imagine and support multiple futures.

Prioritizing context-specific futures grounded in local knowledge systems.

Escobar reframes design as a futures practice, advocating for ontological design that acknowledges how design shapes our experiences and understandings of the world. He explores a "political ecology of design" that moves beyond Western epistemological structures and addresses intersections with race, gender, and colonialism.

Design Shapes and Reflects Culture

Design is inherently political. It plays a central role in our social construction of self and society. The objects and environments we create influence our behaviors, relationships, and even our identities.

As Winston Churchill famously said, "We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us." Similarly, Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa noted that a building is not an end in itself but "conditions and transforms the human experience of reality."

Escobar invites designers to to be mindful of the ideological discourses manifested in design work, and in doing so, being conscious of inadvertently reinforcing dominant ontologies and instead contributing to the imagining of possible futures which centre on inclusive and diverse worlds.

Designing for a Pluriverse

Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" challenges us to rethink design's role in society fundamentally. It calls for a shift from a singular, hegemonic worldview to one that embraces the multiplicity of human experiences and knowledge systems. By adopting a pluriversal approach, we can begin to imagine and create worlds where many worlds fit—a reality that is richer, more equitable, and more responsive to the diverse needs of all beings.

To reimagine what is possible is one of the most important cultural and political acts we can engage in at present.

Arturo Escobar

In embracing this vision, designers become not just creators of objects or systems but facilitators of transformative processes that honor the complexity and diversity of life itself.

In a world increasingly dominated by homogenizing forces of globalization and neoliberal capitalism, Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" emerges as a beacon for alternative ways of being and knowing. Escobar, a Colombian anthropologist and professor, draws from his experiences in the Global South to challenge the prevailing Western paradigms that often marginalize diverse worldviews. His work invites us to reimagine design—not just as a tool for creating objects or systems—but as a practice deeply intertwined with cultural, social, and ecological dimensions of life.

The One-World World Problem

At the heart of Escobar's critique is the concept of the One-World World (OWW), a term borrowed from philosopher John Law. The OWW represents the dominant Western worldview that assumes a single, objective reality—often at the expense of other ways of understanding the world. This hegemonic perspective imposes its own values and systems, effectively silencing alternative epistemologies and ontologies.

The OWW manifests through dysfunctional dichotomies that separate:

Humans from nature

Subject from object

Mind from body

Reason from emotion

Living from inanimate

Human from non-human

Organic from inorganic

These binaries not only limit our understanding but also perpetuate a worldview that justifies the exploitation and marginalization of both people and the environment.

Ontological Design: Resisting the One-World Ontology

Escobar advocates for ontological design, a practice that recognizes the power of design in shaping our realities. By asking critical questions like "Which design?" "What world?" and "What reality?" we begin to see design not as a neutral or purely functional activity but as a world-making practice.

Designers, according to Escobar, must become aware of the "active historical reality"—the ways in which history continues to shape and constrain present-day behaviors and systems. Similar to Michel Foucault's concept of "histories of the present," Escobar emphasizes that our current social structures are products of historical processes that can and should be questioned.

"Designers need to understand the way an ideological discourse manifests in designed objects and built environments. They are only ever designing within wider ontological settings, and everything they design reinforces that ontology if it is not an explicit struggle to redirect it." Cameron Tonkinwise

Epistemologies of the Global South and the Pluriverse

In response to the OWW, Escobar highlights the Epistemologies of the Global South—local struggles and knowledge systems that strive to re-establish balance with nature and among humans and non-humans. These epistemologies challenge the normative dualisms of Western thinking and emphasize relational ontologies where meaning arises through connections with others.

The concept of the pluriverse emerges from this understanding—a world where many worlds fit, embracing a diversity of beings, knowledges, and practices. Moving beyond the Age of Enlightenment's obsession with rationalism and science, Escobar calls for the inclusion of intuition, feelings, and emotions as valid forms of understanding.

He posits that the lived experiences of marginalized communities often create conditions for radically different modes of participation and action-oriented design. Here, local knowledge and insights become the starting point, not an afterthought.

Relational Ontologies and Ancestrality

Relational ontologies recognize that people, objects, and concepts are defined by their relationships and interactions rather than existing as isolated entities. For example, a person's identity is shaped by their relationships with family, community, and environment.

In many indigenous cultures, ancestrality plays a crucial role. Ancestors are seen as an active presence influencing how people relate to land, community, traditions, and the future. This perspective underscores the urgency of integrating ancient wisdom into modern times.

Design as a Space for Transformation

Escobar envisions design as a space for transformation—not as an external force acting upon the world but as an integral part of the world transforming itself. This approach moves design away from a colonizing posture and towards one that acknowledges autonomy, agency, and interdependence.

He advocates for design as a potential mechanism of plurality, by recognizing that design is neither neutral nor universal, we can use it as a tool for intentional creation that includes diverse knowledges and experiences within specific contexts.

Escobar invites us to consider the shift from creating for others—a patriarchal and colonial approach—to creating with others, and ultimately, to all of us creating for ourselves with each other, locating imagination within the context of community, autonomy, and mutual interdependence.

Sociology of Absence and Emergence

Escobar introduces Boaventura de Sousa Santos' concepts of the "sociology of absences" and the "sociology of emergence."

Sociology of Absence: This addresses how certain perspectives, knowledge systems, and social realities are marginalized or erased by dominant structures. These absences are not natural or accidental; they are actively produced to maintain existing power dynamics.

Sociology of Emergence: This focuses on the untapped potential within society for new ways of thinking, organizing, and living. It seeks to identify and legitimize emerging ideas and practices that challenge the status quo.

By recognizing these dynamics, we can begin to recover and include diverse perspectives, fostering a more equitable and comprehensive understanding of the world.

Implications for Design and Futures

Transitioning towards a pluriversal approach requires embracing pluralism in our design practices. This involves:

Challenging the singular, universal future often implicit in mainstream thinking.

Decentralizing Western perspectives to imagine and support multiple futures.

Prioritizing context-specific futures grounded in local knowledge systems.

Escobar reframes design as a futures practice, advocating for ontological design that acknowledges how design shapes our experiences and understandings of the world. He explores a "political ecology of design" that moves beyond Western epistemological structures and addresses intersections with race, gender, and colonialism.

Design Shapes and Reflects Culture

Design is inherently political. It plays a central role in our social construction of self and society. The objects and environments we create influence our behaviors, relationships, and even our identities.

As Winston Churchill famously said, "We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us." Similarly, Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa noted that a building is not an end in itself but "conditions and transforms the human experience of reality."

Escobar invites designers to to be mindful of the ideological discourses manifested in design work, and in doing so, being conscious of inadvertently reinforcing dominant ontologies and instead contributing to the imagining of possible futures which centre on inclusive and diverse worlds.

Designing for a Pluriverse

Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" challenges us to rethink design's role in society fundamentally. It calls for a shift from a singular, hegemonic worldview to one that embraces the multiplicity of human experiences and knowledge systems. By adopting a pluriversal approach, we can begin to imagine and create worlds where many worlds fit—a reality that is richer, more equitable, and more responsive to the diverse needs of all beings.

To reimagine what is possible is one of the most important cultural and political acts we can engage in at present.

Arturo Escobar

In embracing this vision, designers become not just creators of objects or systems but facilitators of transformative processes that honor the complexity and diversity of life itself.

In a world increasingly dominated by homogenizing forces of globalization and neoliberal capitalism, Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" emerges as a beacon for alternative ways of being and knowing. Escobar, a Colombian anthropologist and professor, draws from his experiences in the Global South to challenge the prevailing Western paradigms that often marginalize diverse worldviews. His work invites us to reimagine design—not just as a tool for creating objects or systems—but as a practice deeply intertwined with cultural, social, and ecological dimensions of life.

The One-World World Problem

At the heart of Escobar's critique is the concept of the One-World World (OWW), a term borrowed from philosopher John Law. The OWW represents the dominant Western worldview that assumes a single, objective reality—often at the expense of other ways of understanding the world. This hegemonic perspective imposes its own values and systems, effectively silencing alternative epistemologies and ontologies.

The OWW manifests through dysfunctional dichotomies that separate:

Humans from nature

Subject from object

Mind from body

Reason from emotion

Living from inanimate

Human from non-human

Organic from inorganic

These binaries not only limit our understanding but also perpetuate a worldview that justifies the exploitation and marginalization of both people and the environment.

Ontological Design: Resisting the One-World Ontology

Escobar advocates for ontological design, a practice that recognizes the power of design in shaping our realities. By asking critical questions like "Which design?" "What world?" and "What reality?" we begin to see design not as a neutral or purely functional activity but as a world-making practice.

Designers, according to Escobar, must become aware of the "active historical reality"—the ways in which history continues to shape and constrain present-day behaviors and systems. Similar to Michel Foucault's concept of "histories of the present," Escobar emphasizes that our current social structures are products of historical processes that can and should be questioned.

"Designers need to understand the way an ideological discourse manifests in designed objects and built environments. They are only ever designing within wider ontological settings, and everything they design reinforces that ontology if it is not an explicit struggle to redirect it." Cameron Tonkinwise

Epistemologies of the Global South and the Pluriverse

In response to the OWW, Escobar highlights the Epistemologies of the Global South—local struggles and knowledge systems that strive to re-establish balance with nature and among humans and non-humans. These epistemologies challenge the normative dualisms of Western thinking and emphasize relational ontologies where meaning arises through connections with others.

The concept of the pluriverse emerges from this understanding—a world where many worlds fit, embracing a diversity of beings, knowledges, and practices. Moving beyond the Age of Enlightenment's obsession with rationalism and science, Escobar calls for the inclusion of intuition, feelings, and emotions as valid forms of understanding.

He posits that the lived experiences of marginalized communities often create conditions for radically different modes of participation and action-oriented design. Here, local knowledge and insights become the starting point, not an afterthought.

Relational Ontologies and Ancestrality

Relational ontologies recognize that people, objects, and concepts are defined by their relationships and interactions rather than existing as isolated entities. For example, a person's identity is shaped by their relationships with family, community, and environment.

In many indigenous cultures, ancestrality plays a crucial role. Ancestors are seen as an active presence influencing how people relate to land, community, traditions, and the future. This perspective underscores the urgency of integrating ancient wisdom into modern times.

Design as a Space for Transformation

Escobar envisions design as a space for transformation—not as an external force acting upon the world but as an integral part of the world transforming itself. This approach moves design away from a colonizing posture and towards one that acknowledges autonomy, agency, and interdependence.

He advocates for design as a potential mechanism of plurality, by recognizing that design is neither neutral nor universal, we can use it as a tool for intentional creation that includes diverse knowledges and experiences within specific contexts.

Escobar invites us to consider the shift from creating for others—a patriarchal and colonial approach—to creating with others, and ultimately, to all of us creating for ourselves with each other, locating imagination within the context of community, autonomy, and mutual interdependence.

Sociology of Absence and Emergence

Escobar introduces Boaventura de Sousa Santos' concepts of the "sociology of absences" and the "sociology of emergence."

Sociology of Absence: This addresses how certain perspectives, knowledge systems, and social realities are marginalized or erased by dominant structures. These absences are not natural or accidental; they are actively produced to maintain existing power dynamics.

Sociology of Emergence: This focuses on the untapped potential within society for new ways of thinking, organizing, and living. It seeks to identify and legitimize emerging ideas and practices that challenge the status quo.

By recognizing these dynamics, we can begin to recover and include diverse perspectives, fostering a more equitable and comprehensive understanding of the world.

Implications for Design and Futures

Transitioning towards a pluriversal approach requires embracing pluralism in our design practices. This involves:

Challenging the singular, universal future often implicit in mainstream thinking.

Decentralizing Western perspectives to imagine and support multiple futures.

Prioritizing context-specific futures grounded in local knowledge systems.

Escobar reframes design as a futures practice, advocating for ontological design that acknowledges how design shapes our experiences and understandings of the world. He explores a "political ecology of design" that moves beyond Western epistemological structures and addresses intersections with race, gender, and colonialism.

Design Shapes and Reflects Culture

Design is inherently political. It plays a central role in our social construction of self and society. The objects and environments we create influence our behaviors, relationships, and even our identities.

As Winston Churchill famously said, "We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us." Similarly, Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa noted that a building is not an end in itself but "conditions and transforms the human experience of reality."

Escobar invites designers to to be mindful of the ideological discourses manifested in design work, and in doing so, being conscious of inadvertently reinforcing dominant ontologies and instead contributing to the imagining of possible futures which centre on inclusive and diverse worlds.

Designing for a Pluriverse

Arturo Escobar's "Designs for the Pluriverse" challenges us to rethink design's role in society fundamentally. It calls for a shift from a singular, hegemonic worldview to one that embraces the multiplicity of human experiences and knowledge systems. By adopting a pluriversal approach, we can begin to imagine and create worlds where many worlds fit—a reality that is richer, more equitable, and more responsive to the diverse needs of all beings.

To reimagine what is possible is one of the most important cultural and political acts we can engage in at present.

Arturo Escobar

In embracing this vision, designers become not just creators of objects or systems but facilitators of transformative processes that honor the complexity and diversity of life itself.

Tags

Pluriverse, Ontological Design, Defuturing, Arturo Escobar, postdevelopment theory, Global South

⚒️ | Figma

You might also like

Political Notion

Information Architecture

Political Notion

Information Architecture

Neurodiversity Resources

Concept Development

Neurodiversity Resources

Concept Development

🛠️ Tools + Resources